October 2023 Colloquium

Reimagining Access to Justice and the Rule

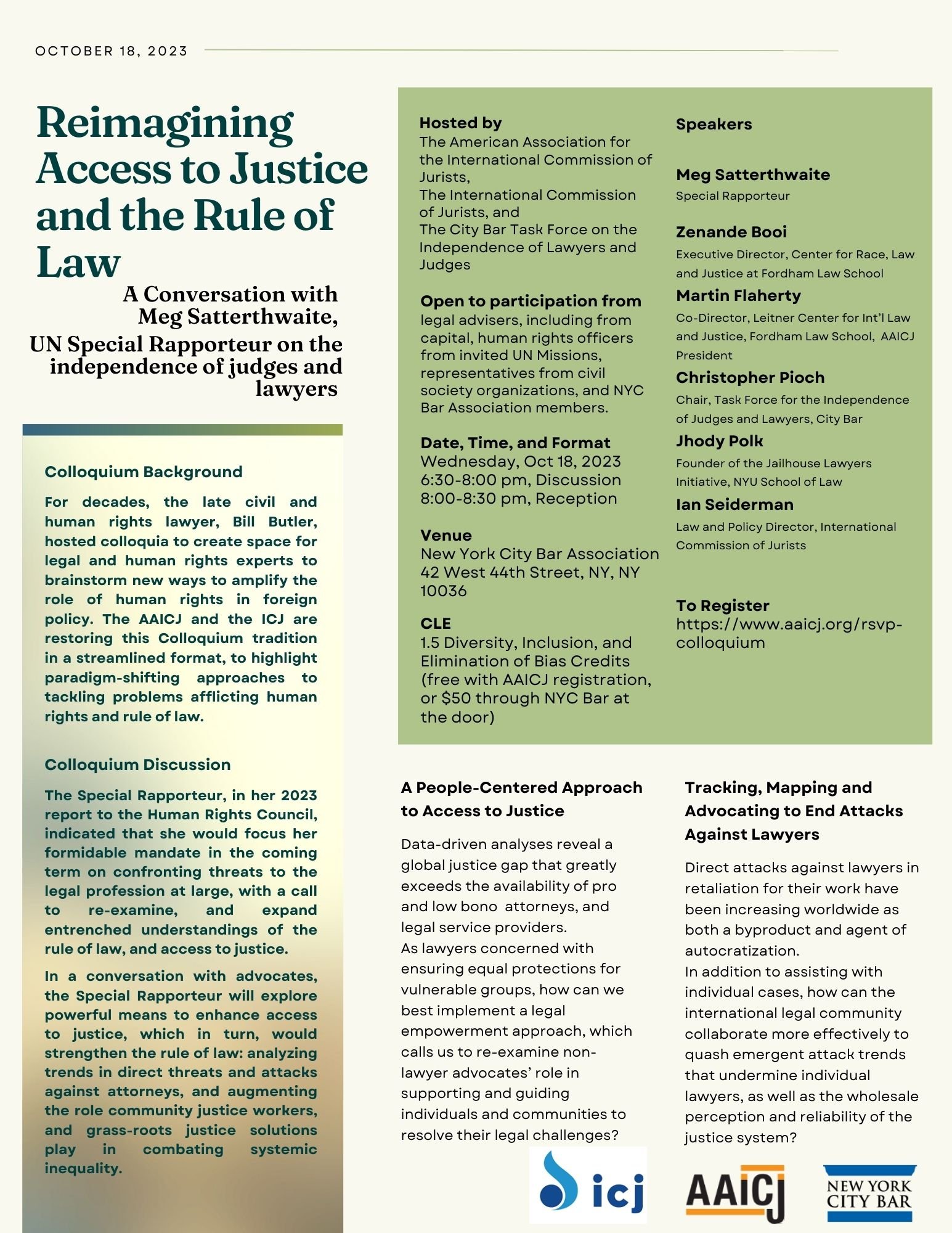

October’s Colloquium meeting managed to draw over 90 people who attended in person at the New York City Bar Association. The meeting opened with a recognition of Bill Butler, in both his legacy of Colloquium leadership, and his decades-long commitment to human and civil rights. This set a warm tone for the conversation, and situated the meeting in a dialogue that stretched back decades.

Attendees were composed of City Bar members; human rights officials from the United Nations and permanent missions; members of New York City government agencies that focus on social welfare and well-being; law professors from various universities; students from several different New York-based law schools, and Columbia School of Public and International Affairs. Importantly, attendees also reflected a host of community justice workers, non-lawyer rights advocates, paralegals, and activists.

It is all too rare to have people with such a range of professional affiliations, backgrounds, and career stages in one room, and it made a palpably exciting atmosphere.

Initially, AAICJ President Martin Flaherty provided an overview of the AAICJ’s present work, and Ian Seiderman, ICJ Legal and Policy Director, explained some of the ICJ’s ongoing work on customary law, and how it relates to legal empowerment. The discussion mostly focused on content highlighted by our three speakers: Special Rapporteur, Meg Satterthwaite, Zenande Booi, Executive Director of Fordham Law’s Center for Race, Law and Justice, and Jhody Polk, the founder and director of the Jailhouse Lawyers Initiative. A summary of their key points is available in the segments below.

Legal Empowerment’s Essential Role in Rule of Law Reform

The Special Rapporteur provided an overview of her report to the General Assembly, A/78/171, which focused on improving access to justice worldwide by calling for the funding and implementation of a legal empowerment approach. The AAICJ’s submission is cited in the report.

Legal empowerment focuses on helping non-lawyers understand and shape the law, to enforce rights and improve outcomes on both the individual and community level. This perspective aligns with what many see as a core component of the rule of law: an engaged public with confidence and real access to the legal system, whether through formal or informal mechanisms, to resolve disputes. A legal empowerment approach to access to justice flourishes in certain places outside the U.S., and it is utilized domestically in some highly successful instances. The reason this is a critical perspective to consider more concretely now, is because even with needed improvements to access to civil counsel, there will likely never come a time in the United States where there are enough lawyers available to assist with basic needs and human rights cases. Legal empowerment focuses on putting law in the hands of people who are directly affected by its enforcement.

-

The Special Rapporteur made a point to emphasize that increasing opportunities for non-lawyers to engage more directly with the legal system does not threaten the essential work lawyers do: an increased legal ecosystem would actually increase lawyers’ functionality by allowing non-lawyer advocates to assist individuals in areas where they have expertise. A frequent, compelling parallel is made between developing a stature and standard within the legal system akin to the role nurses and nurse practitioners play in the medical system, which is not seen as diminishing doctors’ significance.

Providing mechanisms for non-lawyers to hone and develop legal expertise, and guide and advise members of their communities without fear of reprisal would increase racial and economic diversity in who gets to use, and develop the law. It would mean that many more people would have somewhere to turn to with their legal questions, without incurring unmanageable legal fees. Of course, any changes that might be implemented would have to be considered in great detail–but increasing who, and how, people can develop legal knowledge is perhaps the best contemporary solution to ensure improved access to justice.

-

Legal empowerment initiatives are tied to work involving endangered lawyers and judiciaries worldwide under a broader access to justice umbrella. Increased protections for endangered lawyers and the broadened base of legal aptitude and engagement for non-lawyers both serve to materially improve the lives of individuals threatened with violations of human, civil and environmental rights, many of whom are members of communities isolated from centers of power responsible for law-making and adjudication. The Special Rapporteur’s focus on legal empowerment is an acknowledgement of how vital access to justice is to realizing the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals. It also acknowledges how many of these changes can only be implemented with the legal profession’s blessing and participation.

The focus on legal empowerment also recognizes how lawyers’ essential position in establishing and maintaining the rule of law is supported by a thriving infrastructure of non-lawyers: it is time to bring more recognition and support to this active community that so often operates without thanks and recognition, and assumes an unfair risk of accusations of unlicensed practice.

There are many possible applications of a legal empowerment approach to access to justice. The other two speakers on the panel, Zenande Booi and Jhody Polk elaborated on two key perspectives.

-

Zenande Booi is the Executive Director of the Center on Race, Law and Justice at the Fordham University School of Law. Early in her career she clerked at the Constitutional Court of South Africa for the Honorable Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke. Her prior work and research was based with several different South African nonprofit organizations, with an emphasis on land rights and accountability.

Zenande Booi provided a comparative perspective to the discussion of legal empowerment. She emphasized several points, beginning by explaining how customary legal systems need to be permitted to grow, modernize, and develop, much like contemporary common and civil law systems, for the adequate administration of justice for many local and indigenous communities. In nations with a history of colonization, like South Africa, where the dominant legal system was established by the previous colonial power, certain essential matters–like land rights–do not correspond with prior understandings of ownership and title. The consequence of this disconnect in South Africa is draconian: millions of indigenous people lost title to their land. Strong customary legal systems are an essential remedy to correct this ill, and are critical to the protection of human rights.

Zenande highlighted the importance of re-examining and expanding our narrow understanding of who can legitimately take part in the shaping, interpretation, and use of the law - members of marginalized communities should be at the center of these considerations. She emphasized the necessity of finding ways where those who are impacted by legislation are more directly involved in its drafting, and the value of movement lawyering in enabling lawsuits driven by the affected litigants, rather than their lawyers, who tend to involve plaintiffs so far as their facts aid in the case.

-